Music Licensing: Overpriced for Consumers or Barely A Musician’s Income?

In the revolutionised era of music consumption in which listeners have to do the bare minimum to experience their favourite artists, (ie. click a button and stream away on Spotify or some other identical online service, rather than go to the effort to leave the house and pay for a CD/cassette/vinyl/etc.), the artists they passively support are often hardly making a minimum wage. Despite this, those consumers who pay for music licensing to be able to provide music in their public space, or whatever purpose they are supplying, are struggling to afford to even do so.

This impasse between the consumer and the creator is met by the Australasian Performing Rights Association/Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owners Society (better known as APRA AMCOS). In this divide, APRA AMCOS’s role involves “licens[ing] organisations to play, perform, copy, record or make available our members’ music, and…distribut[ing] the royalties to our members”.

In theory, this proves to be a simple, egalitarian system that gives music creators protections and their correct royalty shares. However, increasingly so, more and more companies are coming forward, such as small business owners, with the inability to pay the licensing fees and are as well being forced to pay fines they cannot afford. Calls, protests and suggestions for a change in the pricing scheme have been continuously brought to light but so far have been ignored/rejected by the relevant bodies (APRA AMCOS, PPCA (Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Ltd), One Music, etc.).

How Copyright and music licensing work in Australia

Copyright and music licensing in Australia operate via a simple and effective line of order:

In the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), a “work” or “subject matter other than work” can be protected. In the case of music/recordings, this typically refers to respectively “musical works” (created/owned by the songwriter) and “sound recordings”(created/owned by whomever the recording artist is and whomever else solicited/partook in the recording/performance).

Owner of either copyright protected work or subject matter has the exclusive right to perform, communicate and reproduce the work in any form, as well as negotiate terms and conditions that relay to a form of payment for said services.

Royalties are generated via several means and paid through to the relevant copyright owner party via APRA AMCOS or another licensing body. Two of these important royalties are:

Mechanical royalties - the physical copy of the sound recording (the definition was extended in 2000 by the Digital Agenda Amendments to allow for music files streamed), paying 6.25% RRP to the owner of music and lyrics), and;

Performance royalties - any public performance or communication of the piece, collected by songwriter via APRA (typically at least 50% revenue)).

It is those performance royalties that are cause for conflict in the consumer market.

Performance royalties will be owed whenever a song is publicly performed or communicated. Such settings include background music in a shopping centre, music used on a telephone on-hold system and many more.

It is difficult to determine how many times a particular song is played and when, hence some estimation is put into the copyright payment given to the performer — majority of this calculation is completed by how popular the songs are in respect to each other on any given day. This algorithm may possibly be on an improvement due to statistical data claimed from and provided by online streaming platforms.

For one consumer, it’s enough to pay for a Spotify account and listen to music, however, once that music is used publicly, the consumer is effectively taking responsibility for the effects that music plays in that space. Statistics provided by One Music show that 51% of travel customers will spend more time with their travel agent when there is music playing. As well 78% of patients find waiting in a doctor’s office easier with background music.

Because of the fact that an artist’s creation is being used, the consumer must have a licence to pay the artist for that service, hence APRA AMCOS, PPCA and One Music’s roles come into exertion. A consumer can avoid this situation if they play royalty free music or the radio (as the radio stations already have licences), but a licence must be purchased in order to give the musician the performance royalties they earned. Whilst the licences are deeply tailored for each performance purpose, from head capacity to room size, consumers are becoming indignant when faced with the yearly price of the licence they need to acquire.

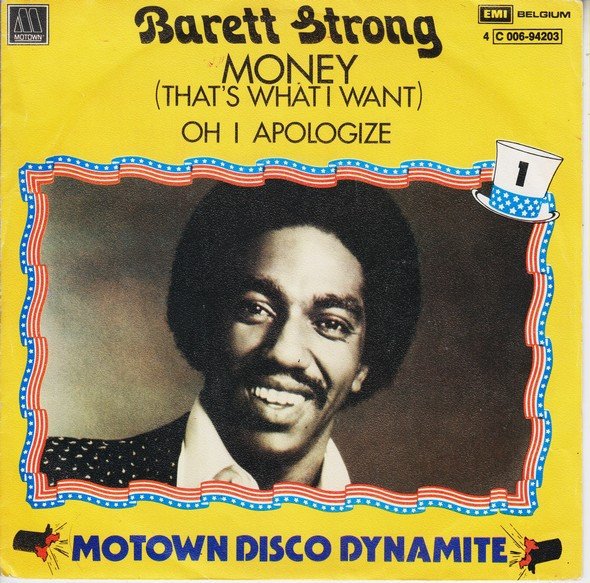

History of the relationship between labels and musicians and how it applies today has proven time again that these record labels and studios will reach excessive heights to get as much money out of musicians and their works as possible. In the 1960s, Motown was an exemplar display of this practice with the infamous case of Barrett Strong’s song ‘Money (That’s What I Want)’.

Strong was the first to record ‘Money’ and co-wrote the piece, yet his authorship was silently removed three years after the writing of the song, resulting in no profits or royalties whatsoever.

It was restored by the renewed American Copyright Act in 1978 but was again removed a year later. The records showed that this stemmed from the direction of Motown executives “who dispute[d] Mr. Strong’s claim of authorship”. Berry Gordy’s (founder of Motown Records) lawyers claimed that this initial registration was result of an administrative error. Moreover, they stated that Strong passed up several opportunities to assert his claim, but he however stipulates that he only ever heard of these alterations in late 2010.

Now he has been blocked the ability to reach his shares into the royalties that came from this coveted, chart-topping hit, as a provision of copyright law in the U.S. states that “he relinquished his rights by failing to act in a timely fashion to contest Motown’s action”.

Whilst this account may seem irrelevant, the business principles apply today. Many parallels are being drawn from the Motown record industry to this period. Ex-drummer of Smashing Pumpkins, Jimmy Chamberlin, made the statement that

“We’re reliving this Motown moment where everyone’s going to wake up and realise it was only because artists didn’t have a place at the table.”

Chamberlin adamantly claims that artist are constantly “at the financial mercy” of record labels, publishing companies and music corporate bodies. He highlights that whilst mechanical royalties were at a high during the Smashing Pumpkins’s successful period in the 1990s, there was much more money to go around than there is today.

Record labels facilitate an instrumental role in grabbing and maintaining radio play for their artists. But there is much to be said for the success found in independent release. Macklemore & Ryan Lewis found fame and success through their YouTube platform. Yes, the group turned to Warner Music Group to get their breakthrough song to hit the radio, but the major difference between this case and that of many other current artists is that Macklemore was sure to retain the song’s rights. This is a step for the right direction as artists across all creative streams are often duped into contractual agreements that attribute many more benefits to the label than themselves.

It’s clear that artists are trying harder and harder to preserve their rights, but in today’s musical economic climate, there is far less money to be given. The advancements of technology and streaming services are fast bringing the costs of distribution to nil, and not at the fault of the platform itself, but rather the implications of the consumption service and the culture of corporate greed.

But now, musicians are not only fighting labels for their rights in an already dismal financial state, but have found a new enemy in the consumers, who paradoxically, want to support them, but just can’t afford to.

The role of consumers

Consumers aren’t given a choice — if they want to listen to music, so they can, and are entitled to, buy it in whichever form they like. However, the lack of awareness surrounding what their responsibilities are as a music consumer is producing more problems, and the number of cases revolving around exorbitant fines and lack of proper licence purchasing continues to rise.

In 2018, ABC News ran a story regarding a local Melbourne bar, Hairy Little Sister, which detailed the performance use of nine popular/rock songs being played without a licence. Judge Julia Baird found the owner, Kristine Becker, having “acted with “disregard” for the rights of the musicians…[she] ignored numerous attempts by the PPCA…to contact her”. Not present in court when Judge Baird made the ruling of $185,000 in damages and costs to be paid, Becker is no longer allowed to play said songs.

This case is a flagrant example of the divide between musicians and their consumers. A vital income stream, the licences and attached fees become essential to the musician’s livelihood and ability to continue to produce more music in the future for their listeners. Yet when the music consumption moves out from solo Spotify headphones to speakers in a crowded bar, the rules change. Why is this becoming a problem?

Many business owners pin the blame on lack of awareness and education regarding these licences, but business registration forms specifically offer these licences in processing. Does the application need to be enforced more, or made more prevalent in current news and social media? Or will it have to become an even bigger problem before someone does something about it?

Music buyers typically pay monthly account fees for services, such as Spotify and Apple Music, which are calculated by the amount of royalties the artists would need to have remunerated to them. These fees are generally affordable for the average consumer, but there is an almost concealed unwillingness to pay more for a licence or fine when they make the listening public.

However, there is a strange readiness to support the artists via different means. With the popularity of live shows, concerts, festivals and more, young consumers are more than happy to spend a few hundred dollars on concert tickets, expensive merchandise, backstage experiences, and more.

This is the next main income source for artists, especially major artists supported by labels. Touring and merchandise become an income with the continued lack of royalties from licences coming their way. Country singer, Lyle Lovett, received no money in royalties when he sold over 4.6 million records; yet he is still considered to have had a successful career. Without this revenue stream, it is clear that artists would be struggling so much more than they already are.

This begs a notion about consumerism in a music corporate domain — we are met with silence when record companies steal from artists legally, but when fans skimp on licences and fees, there is outrage.

It is quick and easy to assume that the power and status of a reputable record label plays an essential part in the untouchable grind of the question. Others are fast to say that the mere negative connotation, or threat, of a ‘fine’ without a licence is enough to scare consumers away.

In reality, it will never be truly clear what the answer is.

What does this mean for the Australian music industry?

Australia is currently caught in the three way divide; the musician — the consumers — the corporate bodies. Between musicians wanting to create music and needing to get paid to do so, and the public unknowingly un-supporting them whilst attempting to do the opposite, and record labels piggybacking a culture of advantageous behaviour, the three parties that are the fundamental foundation of the music industry become caught in an oxymoronic loop.

Musicians can find other means in merchandising and touring, as well as trying to independently represent themselves, but they are at an easy mercy if they are unaware of how to protect themselves, to both the public and the labels. Consequently, consumers are needing to exert greater awareness of their responsibilities as a buyer, but not put the fault to APRA AMCOS’s instructions and other protective organisations.

Ultimately, some people want to make music, other people want to listen to it, and others want to represent it. But without proper copyright practice from all parties, a giant financial mess will assumedly follow.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Disclaimer: this piece of writing was first and foremost created as an examined essay for a University assessment in 2019. It has been re-written and revised to be published as a piece of online literature, but can and willingly be taken down at any time by the author.